Australia's First 4 Billion Years: Life Explodes

Season 40 Episode 10 | 54m 10sVideo has Closed Captions

Fossils reveal how life’s explosion in the ocean was recreated on dry land.

Fossils reveal how life’s explosion in the ocean was recreated on dry land.

Problems with Closed Captions? Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems with Closed Captions? Closed Captioning Feedback

National Corporate funding for NOVA is provided by Carlisle Companies. Major funding for NOVA is provided by the NOVA Science Trust, the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, and PBS viewers.

Australia's First 4 Billion Years: Life Explodes

Season 40 Episode 10 | 54m 10sVideo has Closed Captions

Fossils reveal how life’s explosion in the ocean was recreated on dry land.

Problems with Closed Captions? Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch NOVA

NOVA is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Buy Now

NOVA Labs

NOVA Labs is a free digital platform that engages teens and lifelong learners in games and interactives that foster authentic scientific exploration. Participants take part in real-world investigations by visualizing, analyzing, and playing with the same data that scientists use.Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipRICHARD SMITH: Over four billion years in the making.

An island adrift in southern seas.

It's Australia, the giant Down Under.

A young nation, with all the gifts of the modern age.

But move beyond the cities and an ancient land awaits... One nearly as old as the Earth itself.

Australia is a puzzle put together in prehistoric times.

And the clues that unlock the mystery can be found scattered across Australia's sunburnt face.

I'm Richard Smith, and this is an amazing country.

I'll show you that every rock has a history, every creature a tale of survival against the odds.

Join me on an epic journey across a mighty continent, and far back in time.

Of all continents on Earth, none preserve the great saga of our planet and the evolution of life quite like this one.

Nowhere else can you so simply jump in a car and travel back to the dawn of time.

In this episode...

The world above water has sat silent and lifeless.

But now, armies storm the beaches and biology conquers the world.

It's the battle for life on Earth.

The struggle for legs and lungs, sunlight and shelter, even the quest for sex.

From Australia's ancient stones comes the story of our world.

"Australia's First Four Billion Years: Life Explodes," right now on NOVA.

Major funding for NOVA is provided by the following... SMITH: If Australia seems a little tired and worn, it's because she's seen a lot happen over the course of her long life.

In the last episode, our journey down the road of time began with the Earth's fiery birth four-and-a-half billion years ago.

We passed the first fumbles of life in the waters skirting Australia's ancient shoreline.

Along the way, we've seen the planet change from poisonous to pleasant, and the first animals begin to swim the seas.

Yet save for a thin smear of slime and bacteria along the soggiest of margins, all the continents themselves had lain bare for over four billion years.

In terms of the lifetime of a continent, Australia and the world around it is still an infant, still attached to its motherland-- the great supercontinent Gondwana-- and still a blank canvas on land.

GPS VOICE: Your destination is the Paleozoic.

SMITH: Now with 90% of Earth history behind us, it's time for conquest.

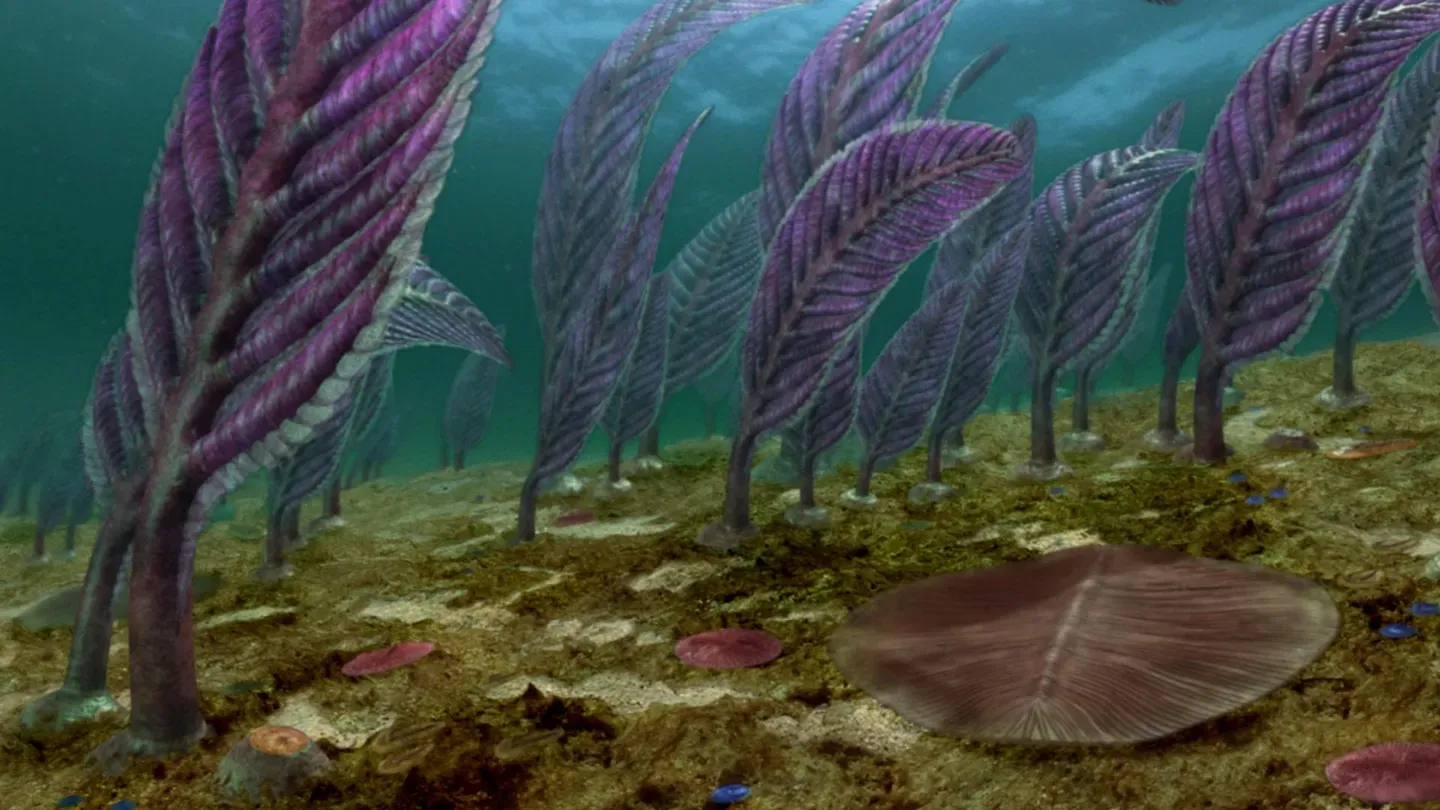

The tremendous explosion of life that began in the oceans of the Cambrian was still going strong at the dawn of the Ordovician, the second of the six great periods that make up the Paleozoic.

And it was in Ordovician oceans that a second wave of animal experimentation began as well, one that ultimately would lead to the first Australians coming ashore.

With the seas now crowded with life, the first tentative footsteps onto land were not far away.

Now at the time, Australia was just one of an exotic collection of lands, including India, Africa, South America and Antarctica, that today we call the supercontinent Gondwana.

Australia's position was just about here, right at the tip, just north of the equator, and mostly underwater.

Oceans were rising around the planet, and seawater flooded in across parts of Central Australia.

At the time, the sea of sand we know today as the Simpson Desert was slap bang in the middle of the Larapinta Seaway, a tongue of warm ocean water that licked right across the country.

Back then, this bouncy drive would have been a bumpy boat crossing.

As the rising waters swept in, they carried a rich bloom of plankton-- food for some of the earliest fish to swim in the sea.

And they swam right here, right above me.

The last vestiges of the old Larapinta seafloor lie tumbling from the top of the mesa-shaped hills of the Simpson Desert.

Even in the best of seasons like this, the Simpson is a harsh, unforgiving landscape.

Now you probably wouldn't expect to find the world's earliest fish in the dead center of the driest inhabited continent on the planet today.

But it was on the side of this hill in the Simpson Desert where the fossil of Arandaspis lay waiting to be discovered.

We only know Arandaspis from the bony head plates and body scales it left behind... enough to tell that this was a fish with a simple tail and no real fins.

Nor did fish like Arandaspis have jaws, or even teeth.

They probably just slurped in whatever morsels they could find.

But don't underestimate the significance of this fish.

This was an animal with a backbone.

It's one of the first vertebrates, so we can all trace our ancestry back to an animal like this.

But giant invertebrates ruled these Ordovician seas, and to them, Arandaspis was just a bite-sized snack.

While the first fish took to swimming out of danger, their invertebrate foes would soon be flexing their leg muscles in a different way.

Time to put the foot down and head for the seaside in the Silurian.

On a remote stretch of the Western Australian coast, the 21st-century Indian Ocean eats away at an ancient Silurian shoreline.

Wind and water have exposed the burrows of long-gone animals in the sandy coastal cliffs.

The original inhabitants of the burrows remain a mystery, but not the predators attracted by such rich pickings along the prehistoric shoreline.

Clues to their identity are revealed in the rocks of nearby Murchison Gorge.

Here the river has sliced deep into the Silurian past.

The Murchison Gorge back in the Silurian wasn't a gorge at all, of course.

It was a vast estuarine flood plain with rivers winding down from the hills in the distance carrying sand into the sea.

But for the first time in the history of the planet, those Silurian shorelines down there were alive with animal activity.

This may not have been a good time to take the kids to the beach.

Armies of sea scorpions were massing in the shallows.

Known to paleontologists as Eurypterids, some of these intimidating arthropods grew as long as a man is tall.

And they bristled with armored legs and fearsome claws.

Far less threatening was this bloke.

Kalbarria was probably an ancestor of modern crustaceans and grew about as long as a king prawn.

Whether in search of food, a safe place to mate or simply to avoid the nasty neighbors, Kalbarria clambered ashore... and left clear imprints of its many tiny feet in the rocks.

A descent into Murchison Gorge takes you back to those ancient Silurian shorelines.

Down here, it soon becomes clear that the sea scorpions followed Kalbarria ashore.

This is what we call "Track Central."

I can see why.

Yeah.

There were tracks everywhere.

This is probably the best site in the park to look at these eurypterid tracks.

Our animal's come through here.

So, in shallow water.

Shallow water.

Been slipping and sliding as it comes around the corner.

That's exactly right.

But here.

I mean I can see, clearly there's this kind of sloppy looking track here, but once you come over here, you start seeing really discrete footprints.

Clear, graphic demonstration of a creature walking out of the water and onto dry land.

And where we are here in the depth of the gorge, we're in the oldest of the Silurian sediments in this area.

Quite an historic little spot you've got here.

Very, very.

SMITH: These trackways offer some of the oldest evidence for animals on land.

And even though these formidable beasts could not stray far from the water's edge, a beachhead had been established.

So this seems to be how the animal invasion of the land began: with a scary assortment of arthropods with attitude slinking and scuttling ashore onto the wet sands of a new frontier.

But this wasn't just a continent to exploit; there was a whole planet for the taking.

Waiting beyond the breakers were all the wide, brown lands of Earth.

Australia, already under animal assault, found itself center stage for the waves of invasion and conquest that would follow.

But animals were not going to get far inland without help from plants.

They, too, came out of the sea, first as slime, then as low, spreading things that clung to dampness.

Seaweeds captured the shoreline, then tiny forests of lichens, liverworts and mosses pioneered the move inland.

Today, we take for granted the plants around us.

It's their oxygen we breathe, their food we eat.

But the land can be a tough, dry place to live, and any plant going to make it big out here needed a thick skin and a little internal fortitude.

Just such a plant first took root somewhere around here.

(blowing air on rock) If you thought that this was just another ordinary roadside cutting on a pretty but ordinary country road, well, of course, you'd be dead wrong.

It was here near Yea in Victoria that fossils of some of the world's earliest land plants were found.

Indeed, these rocks contain the first signs of the greening of Gondwana.

Just amazing.

This is Baragwanathia, possibly the oldest true land plant in the world.

Not much to look at perhaps, but with green leaves and a stem to carry sap internally and to support its weight, the world above water was its oyster.

In life, it would have looked much like this.

This is a lycopod or club moss, as was Baragwanathia, rising out of the water in a coastal bog in Queensland today.

These are the direct descendants of the green revolutionaries who changed the face of the planet.

If you look closely, you can see many of these Silurian-type plants still clinging on in damp corners around the country.

Here's a rainforest Selaginella, a tropical tassel fern, a club moss in Tasmania, even a Psilotum in Sydney.

Plant life had by now engineered a solution to the ultraviolet radiation that had been sterilizing the Earth's surface: an ozone layer built from excess oxygen.

The low, spreading thickets provided the perfect humid cover for other arthropod forms like millipedes, centipedes and mites to make the transition to land complete.

Some mollusks even brought their own homes, because it was still not a very welcoming place.

While life was exploring the fringes, most of the Gondwanan supercontinent was dry, probably still quite bare and almost certainly windy.

The Larapinta Seaway had receded, leaving much of what is now Central Australia resembling the Sahara Desert.

And that desert became mountains.

Titanic tectonic forces operating over a span of 150 million years buckled the earth and pushed great folds of rock into the air.

In their heyday, Central Australia's MacDonnell Ranges would have been a mountaineer's dream-- as high, it's thought, as any on Earth today.

But Australia would never experience mountain-building on this scale again.

After a near eternity of erosion, the diminished remnants of the MacDonnell Ranges still run in long, jagged wrinkles across the heart of Australia.

From the air, they protrude into this ancient landscape like the bony skeleton over which the dry skin of a tired continent is draped.

All other continents boast mighty mountain ranges: the Rockies, the Alps, the Andes, the Himalayas.

But they are all relative newcomers and mostly still growing.

What sets Australia's landscape apart is its venerable antiquity and its great flatness.

LISA WORRALL: Australia is actually quite remarkably flat.

And when you look at it from space, it's not just flat, but it's apparently saucer shaped.

SMITH: It's a saucer that holds many secrets for geologist Lisa Worrall.

Her interest is not so much the bedrock of the Outback but the story of all its eroded remnants accumulated over a vast gulf of time.

WORRALL: We know parts of Australia have been exposed for millions if not billions of years.

WORRALL: We are partway through an ongoing geological story.

The rivers that in Australia are mostly draining inland, are actually losing or have lost the ability to carry sediments out and down into the seas, so inland Australia is filling up with sediments.

SMITH: Outback Australia is drowning in sand.

Head towards the coast in any direction from the Red Center and you cross oceans of these old, weathered sediments.

It's the sort of landscape you should expect from the flattest continent on the globe.

Traveling northwest, it's 700 miles before you reach the next significant patch of high rocky ground... the Kimberley.

While mountains were still pushing skywards in the continent's heart, up here in Purnululu National Park, others were already wearing down to nothing.

(distant echo of man singing "Waltzing Matilda") Epic tales of erosion and recycling lie behind most geological features in the Australian landscape.

The sands and gravels that made the Bungle Bungle Ranges started arriving here about 375 million years ago, dumped by rivers that wore away high lands far older and now long gone.

This landscape was already secondhand long before the rocks began eroding away into the famous striped beehive domes we see today.

The distinctive striping of the rocks here is a dead giveaway to how the Bungle Bungles were formed: layer by layer as mighty rivers washed sediment from distant mountain ranges to fill the basin.

This unfolding landscape is a two-toned testament to change, left as a parting gift by rivers that ran down into a Devonian tropical sea.

300 dusty miles to the west of the Bungle Bungles and you can run down to that same ancient sea, once home to some of the most spectacular tropical reefs on the planet.

Surprisingly, you can still visit these reefs today.

I'm standing at the base of the Great Devonian Barrier Reef.

These towering limestone cliffs were once towers of life rising into the clear sunlit waters of a colossal reef system that once circled the Kimberley.

SMITH: In both size and significance, the Devonian Reef rivaled modern Australia's Great Barrier Reef.

Its limestone ramparts were once festooned with crinoids and corals, sponges and seasquirts, and many other creatures still found clinging on in tropical waters.

That Devonian life has gone, but the great reef walls still stand to this day.

It's easier to see from the air.

In the same way that the Great Barrier Reef fringes the Queensland coast today, the Great Devonian Reef skirted in a sweeping curve around the Kimberley hinterland for perhaps 600 miles.

Reef after reef line up across the landscape as if a giant bath plug had been pulled.

At Tunnel Creek, one such stream has carved its way right through the Devonian limestone range.

It's a deliciously cool change from the sweltering heat outside and offers dark access to the very heart of the reef itself.

A whole suite of reef-building organisms built this great Devonian reef above me.

You can see a lot of their ghostly remains in the rocks still-- sponges, stromatolites, corals, strange extinct things called stromatoporoids.

But the real stars of the show here weren't the things that made the reef, but the things that swam around outside it.

Things with fins.

Because this was the great Age of the Fishes.

It was in the Devonian that for the first time, fish filled the oceans.

Fish of all shapes and sizes.

Just not quite the shapes and sizes we see today.

Like the reefs themselves, the fish of the Devonian northwest are amazingly well preserved, protected in limestone nodules scattered across nearby GoGo Station.

You don't get a lot of bites around here.

About one nodule in every thousand yields a good fossil strike.

But whenever you catch a GoGo fish, it's always something special.

Oh, wow.

That's a lot of bone.

That's all bone there, some very large plates.

What do you think that is, Gavin?

It's clearly a large placoderm, probably a big arthrodire.

SMITH: Kings of the Devonian seas were the placoderms.

Fish had moved on since the days of Arandaspis.

Now they had jaws, fins and teeth to go with their bony head plates.

GAVIN YOUNG: The front part of the body was covered in these bony plates and then the tail would be pretty much sharklike.

They were in fact very agile, successful predators and they had a highly developed sensory system.

Some of them had electrosensory perception like modern sharks and rays.

SMITH: Many of these fossil features have been preserved in fabulous 3-D. Oh, look, there's some ridging.

SMITH: The GoGo nodules have protected the fossils from being crushed.

Do you think it might be a Holonema?

A nice bath in acid is going to clear it up.

Even soak it in some water and scrub it with a toothbrush.

I don't know.

If I'm not getting a shower at night, this fish certainly isn't.

SMITH: It's only once the limestone nodule is dissolved away in acid in the lab that the fossilized fish within come back to life in astonishing detail.

Scales, teeth, eye sockets, brain cases, bones and fin rays, the fish are all so fabulously well-preserved for their age that even soft body bits can be made out.

In more ways than one, these are pretty sexy fossils.

KATE TRINAJSTIC: Well, this one here is particularly interesting because it is one of the few male fossils we have.

We can tell that because it has this clasper.

Like a shark?

Very much like a shark.

SMITH: This bony tube structure is the oldest confirmed male appendage: a fishy private part for impregnating a female.

The Devonian was an important time for vertebrate life, with many biological experiments underway, including the all-important vertebrate sex.

Even today, sex in the sea can be a bit of a hit-or-miss affair, a trade-off between precision and plenty.

Without coupling and live birth, vulnerable progeny sink or swim on their own.

Not a strategy destined for success on land.

This is a portrait of the world's oldest preserved mother with child, and we have the fossil to prove it.

This is perhaps our most famous discovery to date.

This is the mother fish, and this is the real kind of clincher we had that you could have live birth.

And it's this little structure here right around the bottom, and that is the umbilical cord which is attaching the mother to her unborn embryo.

My goodness.

That's the world's earliest umbilical cord we know of?

That is the world's earliest evidence of live birth in any vertebrate.

SMITH: Our backboned ancestors were making all the right moves.

Already on the road to becoming social, smart and sexy.

And they were everywhere.

As rain fell on Australia's newly constructed east, rivers ran back down towards the sea, filling the freshwater lakes and backwaters of the new coastal landscape.

Throw a line into one of those Devonian rivers and you would have caught plenty of fish that looked almost identical to this.

Whoa!

Hi, big guy.

Well, look at you!

Aren't you something special?

Now, this is something truly special: a living link to our fossil past.

It's the Queensland lungfish, Neoceratodus forsteri, and I'm trying to hold him, I hope.

Now, he is the most primitive of the handful of lungfish that still swim on planet Earth.

Think about it for a moment.

These guys were already ancient history 100 million years before the first dinosaurs walked the Earth.

And if you're worried about that fish-out-of-water thing, these guys are called lungfish for a reason: they're built for it.

There you go, matey, off you go.

Thank you.

When lungfish moved from the sea into freshwater in the Devonian, they brought with them the ability to breathe with or without gills when the going got tough.

It's a skill that still stands these remarkable living fossils in good stead.

They live on in just a few river systems in southeast Queensland.

And when oxygen levels fall, they can switch to gulping air from the surface.

It's a strategy that has doubtless allowed them to struggle through more than one Australian drought.

Not all fish have been so lucky.

As far as we can tell, drought is a problem that has plagued the country for at least 360 million years.

We know this because in 1955 the local council sent a bulldozer to smooth out a bad bend on the Canowindra to Gooloogong Road.

Well, the bad bend in the Canowindra to Gooloogong Road is still here.

And you wouldn't know it to look at it, but I've just parked right on top of one of the most spectacular Devonian freshwater fish sites in the world.

The road works inadvertently lifted the lid on Australia's oldest known Outback waterhole.

When a paleontological team returned to open the site, thousands of fish tumbled out.

They were lying on the slabs just as they had been the day they all died together when their waterhole dried up.

Like their saltwater GoGo cousins, many were armor-plated placoderms.

There were lungfish here as well, and another related group of fishes with four-lobed fins that we humans should be very thankful for.

Of the 4,000 or more fish uncovered on these Canowindra slabs, this one is special.

It's been given the name Canowindra grossi, after the town, of course, but its real claim to fame are the features it shares with those fishlike animals that were leaving the water behind.

A single pair of external nostrils suggests it, too, could breathe with both lungs and gills.

And it was one of the lobe-finned fish, a group with four limblike fins with a bony internal structure we can recognize in our own arms and legs.

It's not hard to imagine that somewhere in the drying Devonian waterhole at Canowindra, at least one of those fish might have got away... by walking onto land.

And this is why: hard evidence in the form of fossilized four-legged footprints of about the same age and found near the Genoa River in Victoria.

It was a different Genoa River, but these early fishlike tetrapods, about three feet long, were among the first animals on Earth to feel the sand between their toes.

It's not hard to see how the evolution of walking limbs might have come about.

Many Australian fish species today are still testing out ways of getting about without swimming.

This is the aptly named handfish, hopping and skipping its way along the Derwent Estuary in Tasmania.

And this, that master of the tropical mangrove, the mudskipper.

However they'd managed it in the first place, amphibians soon walked out into the botanical wonderland of the Carboniferous.

The Carboniferous saw all sorts of new plants putting down roots and pumping out oxygen at levels the planet had never seen before.

Huge forests, especially in the Northern Hemisphere, helped push up oxygen levels in the atmosphere perhaps 50% higher than today.

The extra oxygen saw some invertebrates grow to enormous sizes.

It allowed millipedes the size of snakes to scuttle across the land and insects as large as seagulls to take to the air.

The rich insect pickings on offer must have favored the spread of the amphibians now moving through the landscape.

But like their froggy descendants today, these ancestral four-legged animals needed to return to water to reproduce.

Sometime in the Carboniferous, the first reptiles overcame this limitation.

Wrapping their eggs in a membrane blanket with a hard outer shell, reptiles could take a watery egg with them on their travels.

It was a solution so successful that it allowed the many contemporary Lizards of Oz to still claim the arid Australian Outback as their own.

There was yet another Carboniferous legacy left out here.

The greening of the Earth began to at least partly turn Australia red.

The highly oxygenated atmosphere began to rust the iron-rich soils and rocks of the Outback.

And some rocks out here are bigger than others.

SMITH: It's very impressive.

WORRALL: It's a fabulous monolith, isn't it?

It's justly famous for being the largest bit of rock, lump of rock in the world.

And it's just gorgeous.

SMITH: And it's very red, the color of weathered iron minerals like hematite.

WORRALL: Many of the rocks of Australia are rusted.

We know that we had oxidizing rocks back to around the Permo-Carboniferous.

That coloration of the landscape is in fact very old and very persistent.

(thunder) SMITH: But at the end of the Carboniferous, just as world domination lay within the reptile's grasp, the changing world threw up another great climate challenge.

The drift of Gondwana saw Australia heading south and getting colder.

It was more than just the location.

The Earth had slipped into another ice age.

And Australia was covered in more ice than it would ever see again.

By the time we reached the Permian, a deep chill had settled in.

Ice carved its calling card on the country.

Nowhere more clearly than the Fleurieu Peninsula in South Australia.

The bedrock here was scoured by glaciers.

All these long scratches and grooves in this smooth surface were gouged by rocks and debris being dragged along at the bottom of an ice sheet, flowing in this direction.

What these rocks are telling us is that clearly, if you looked to the south of Australia back in the Permian, you wouldn't have seen the open ocean we see today.

If you looked back that way, you would have seen the mountains of Antarctica.

It's incredible to think that if you traveled to Australia in the early Permian, the landscape probably looked much like this over at least the southern half of the continent.

Evidence for ice can be found stretching across the country from the Kimberley to the coast of Tasmania.

But this cold landscape was not frozen solid like Antarctica.

It was seasonally cold, more like a northern Alaska or Canada.

Well, Permian Australia might have been freezing cold, but it was far from lifeless.

These remarkable rocks on Maria Island are just stuffed to the gunwales with shellfish.

And nearly every one of the animals in the rocks here, and in the rocks behind me, and the cliffs in the distance, belong to one species of clam-- this one, called Eurydesma.

What Australia's Permian ocean lacked in diversity, it made up for with abundance.

Life crowded the sea floor.

It was the same story on land.

And the proof can be found hidden underneath Australia's moist eastern seaboard... much of it right under modern Sydney.

Beneath the Eucalypt forests that surround the city of Sydney today lie cool-climate forests, far more ancient.

Welcome underground, gentlemen.

Ground floor: the Permian.

I'm heading half a mile down into a coal mine at Helensburgh on Sydney's southern outskirts.

The seams of rich black coal here have been mined for longer than any other in the country.

What you are looking at here is the exhumation, half a kilometer underground, of the dead, black graveyard of a a vast swampy forest that once stretched right across the Sydney basin.

It's hard, messy, noisy work, but there is treasure in this coal: the raw energy of fossilized sunlight.

Half the energy used to light Australian homes, fuel industry, cool beer and power this program comes from Permian plants buried faster than they decomposed over a quarter of a billion years ago.

When scientists looked closely at these coal seams, they found something not seen in the Australian forests growing so far above me today.

The fossil leaves they encountered were found in alternating, repeated layers.

Every autumn, it seems, these now blackened Permian coal forests were once a riot of color.

One tree, above all others, dominated the Permian forests: Glossopteris.

Glossopteris had solved another part of the problem of reproducing on dry land by encasing its embryo in a protective seedy shell.

So successfully, it turns out, that fossilized Glossopteris leaves are the botanical signature of all Gondwanan lands.

The planet had come of age in the Permian.

Here was a world with great oxygen-producing forests, inhabited by animals with four legs.

Insects had taken to the skies, and the seas were brimming with animals.

Life on Earth was going swimmingly well.

And then, suddenly, everything went diabolically wrong.

Well, the Permian came to a sudden and very sticky end right here at the greatest extinction boundary in the planet's history.

Now, this black coal is the last coal to have been deposited anywhere on Earth in the Permian-- the last of the great Gondwanan Glossopteris swamps.

But it also marks the bitter end for over 80% of all species alive on the planet at the time.

This truly was the world's greatest cataclysm.

This figure is conservative.

Some estimates have 95% of all species dead and gone, wiped out in a geological blink.

The trigger, it seems, did not come from outer space, but from underground.

It's now thought massive volcanic eruptions in Siberia pushed CO2 levels sky-high and the planet into a runaway greenhouse crisis.

These were the days when our living Earth nearly died.

Acidified and stagnant, great swathes of the ocean festered.

Toxic bacteria took over from plankton, and deadly hydrogen sulfide spilled into the skies.

But with change-- even of the calamitous kind-- comes opportunity.

And the Earth would soon echo to the thunder of giants.

the next episode of "Australia's First Four Billion Years," dinosaur hunting Down Under.

Big footprints-- one there, another one there.

Peer into the belly of the beast.

And inside the stomach we can see the vertebrae of its meal.

Come face-to-face with bizarre creatures of a lost world.

It's almost as if there's an independent experiment in evolution going on here.

"Monsters," next time on "Australia's First Four Billion Years" on NOVA.

Ma ♪ ♪ To order this program on DVD, visit ShopPBS or call 1-800-PLAY-PBS.

Episodes of "NOVA" are available with Passport.

"NOVA" is also available on Amazon Prime Video.

♪ ♪

Australia: Life Explodes Preview

Video has Closed Captions

Preview: S40 Ep10 | 30s | Fossils reveal how life’s explosion in the ocean was recreated on dry land. (30s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipSupport for PBS provided by:

National Corporate funding for NOVA is provided by Carlisle Companies. Major funding for NOVA is provided by the NOVA Science Trust, the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, and PBS viewers.